Dr Sullivan interviewed and quoted in this Buzzfeed article.

________________

Already dealing with backlash from employees who object to working with government agencies, major tech companies are now facing criticism from a new source — prospective hires.

“I had been reading a lot in the last month or so about their providing tech to Palantir, and their warehouse labor practices, and their potential large contract with the Department of Defense,” Meshulam told BuzzFeed News.

In his email to the recruiter, which he later tweeted, Meshulam wrote, “I am not willing to consider opportunities with Amazon as long as it sells facial recognition technology to law enforcement agencies, and enables ICE’s separation of immigrant families by providing technology to Palantir.”

Meshulam’s refusal to consider working for Amazon until the company addresses ethical concerns that employees and outside watchdogs have raised is part of a larger trend. Using the hashtag #TechWontBuildIt, a handful of tech workers on Twitter have shared how they’re rejecting interviews with companies like Amazon and Salesforce, either because they disagree with the company’s practices or don’t want to help build its products.

Trained programmers, software engineers, and data scientists are in notoriously high demand in the tech industry. Companies spend millions of dollars on recruiting efforts every year and offer a dizzying array of perks and benefits (lengthy parental leave, infertility treatment, free beer, unlimited vacation) to entice workers. That means prospective employees have leverage — and some of them are trying to use it to get these companies to change their ways. The actions of a handful of individuals are unlikely to steer corporate policy, but the trend could signal a looming recruiting pipeline problem if the companies don’t change tack.

“Literally, they get a job offer twice a week,” said San Francisco State University professor John Sullivan of the demand for qualified tech workers. As a result, whether its diversity or sustainability, “whatever people care about, you have to care about it too.”

“Recruiters don’t really track it, so they don’t have a data sheet saying, ‘We’re losing people because of this,’” said Sullivan, who is also a recruiting adviser to companies, including Google and Facebook. “They haven’t made the connection, but it’s certainly real.”

Reached for comment, a spokesperson for Amazon wrote via email, “Over the past three years, Amazon has had millions of job applicants and grown by more than 300k employees. We welcome a variety of views on a wide range of topics, and we’re pleased to see independent data that shows Amazon is a sought after and great place to work.”

Salesforce declined to comment on this story.

There has been something of a tech employee awakening of late: Thousands of workers at Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Salesforce have signed petitions asking management to cancel contracts with government agencies, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Customs and Border Protection, and the Department of Defense. In June, Google employees succeeded in getting the company to agree not to renew its deal to help the Pentagon build AI tools for drone warfare. Communicating with recruiters is one way for tech workers to wield influence even if the companies aren’t currently employing them.

That’s why Will, a software engineer in the Midwest who asked only to be referred to by his first name, said he knew he couldn’t accept an interview with Amazon after the company sent him a recruiting email, even though he’s actively looking to move to the West Coast. “If it was a different company that wasn’t so morally tainted, I probably would have considered it,” he told BuzzFeed News.

Instead, Will wrote a quick reply. “While I’m sure this would be a great opportunity, I have no interest in working for a company that so eagerly provides the infrastructure that ICE relies on to keep human beings in cages, that sells facial recognition technology to police, and that treats its warehouse workers as less than human,” he wrote.

Will’s message was written on impulse, and he didn’t realize other people had done the same thing until the saw their tweets. That realization made him feel empowered. “The fact that someone else independently had the same idea sort of implies there are probably a lot more people doing the same thing,” he said. “If there’s a significant amount, I feel like the recruiters are going to have to say something at some point, or that they’re at least more likely to report it to higher ups.”

The recruiter at Amazon never responded to Will’s message, but other tech workers who sent similar interview declines did receive answers. Meshulam, the engineer from Chicago, said the recruiter he was in contact with thanked him for his candor and said he’d get back in touch if the employee petition made any headway.

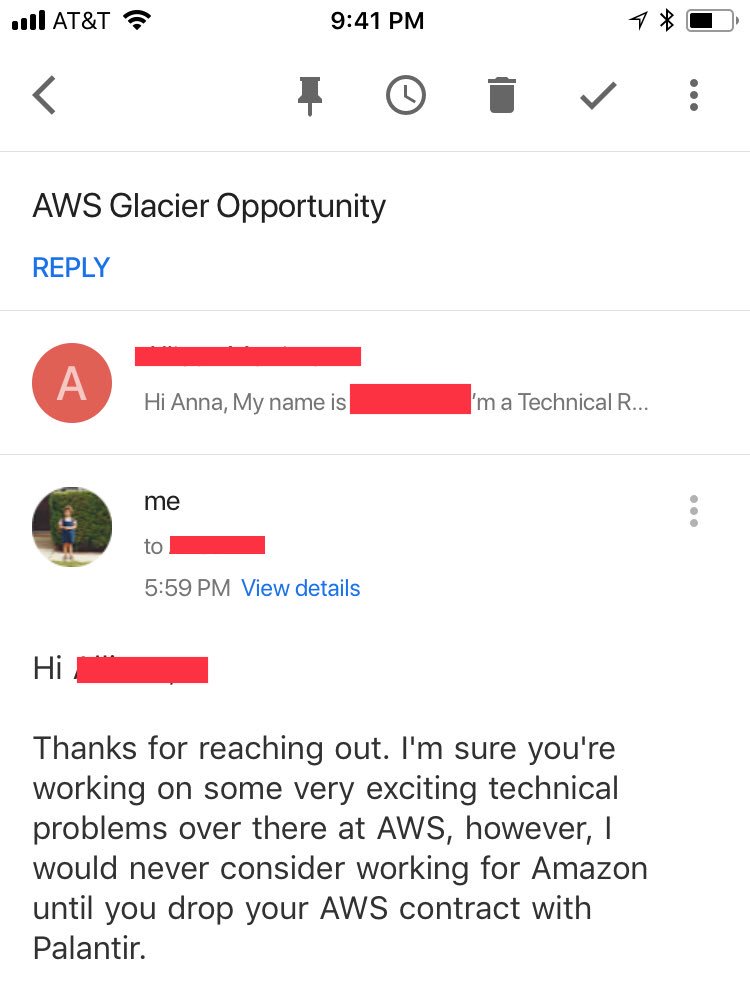

Dropbox engineer Anna Geiduschek, whose tweet about her rejection of an Amazon recruiter inspired Meshulam, was surprised by the answer she received.

“Wow I honestly had no idea,” the recruiter that contacted her wrote in a response. “I will run this up to leadership. Usually they are really proactive about these kinds of things.”

For Geiduschek, the recruiting email from Amazon felt like a powerful “personal leverage point,” an opportunity to share her disapproval of what Amazon is doing in a way that might actually get people to listen.

“If it’s just me, it’s not going to change,” she said. “But if a tenth of the workforce was threatening to quit, or they felt like 10% of their recruiting pipeline was turning away when they would have otherwise taken a job, then I think it really would become on a lot of executives’ radars.”

The likelihood is fairly low that tech executives would be seriously concerned over a handful of engineers turning down job opportunities, says Will Hunsinger, CEO of Riviera Partners, a tech recruiting firm with offices in San Francisco and Silicon Valley. “For every engineer or executive that takes a moral or ethical stand, there’s 99 on the individual contributor side and nine on the executive side who are … going to engage with the company if that’s where they want to work,” he said.

But Sullivan, the SFSU professor, said in the last two years, he’s increasingly hearing from students who say they’d flat-out refuse to work for tech companies, especially Amazon. (“You get the warehouse stories number one … and facial recognition for some reason is huge,” he said.)

“If you talk to college students and say, ‘Do you want to work for this company?’ they say, ‘No way, not ever, it’s a deal breaker.’ But then you talk to recruiters, and I don’t hear them say, ‘We have to change our way of managing because it’s affecting our ability to recruit,’” Sullivan said.

Sullivan estimates that Uber’s public meltdown over sexual harassment and discrimination cost the company around $100 million in recruiting because of talent that went elsewhere. While in the short term companies might choose lucrative government contracts despite losing a few new recruits, in the long term, the real cost will become apparent, he said.

“At some point six months or a year from now, [HR is] going to get a yell from executives saying, ‘There’s a connection, we need to stop doing business this way or sell it better, because people have too many choices,’” he said. “Executives think business is business. That’s certainly Google’s response — ‘We make a lot of money out of this!’ Facial recognition at Amazon, they’re like, ‘This could be the future!’ Executives don’t want to stop it, and they don’t know how to handle the fact that employees say, ‘No, I won’t stand it.’”

Dr John Sullivan Talent Management Thought Leadership

Dr John Sullivan Talent Management Thought Leadership